Week 10

Black Immigrants in America

SOCI 231

Lecture I: November 4th

A Quick Reminder

Response Memo Deadline

Your seventh response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM today.

A Quick Reminder

Final Paper Proposal

Final Paper Proposal Deadline

Your final paper proposals are due by 8:00 PM on Friday, November 22nd.

A Quick Reminder

Final Paper Proposal

More details will be provided on Wednesday.

A Quick Reminder

The Election Is Here

Black Immigrants and Black America — Tod Hamilton

A Growing Subpopulation

By 2014, approximately four million black immigrants were living in the United States. At that time, 10% of the overall immigrant population identified as black and 9.2% of the population who identified as black were immigrants … If the growth in black immigration continues, this group and their descendants will play a significant role in driving the social and economic trajectories of the US black population over the next several decades.

(Hamilton 2020, 296, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A Growing Subpopulation

While Caribbean immigration dominated black immigration throughout the 1980s and the early 1990s, African immigrants drove black immigration during the late 1990s and the first two decades of the twenty-first century … By 2013, 1.3 million black African immigrants were residing in the United States. While Caribbean immigration also increased between 2000 and 2013, growing by 33%, African immigration increased by 137% during the same period.

(Hamilton 2020, 296, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A Growing Subpopulation

A Growing Subpopulation

The previous map may, of course, be a tad misleading.

A Growing Subpopulation

Recent Data from the Pew Research Center

A Growing Subpopulation

And yet, the unique experiential trajectories of Black immigrants in America are rarely the focus of research on social integration

(Hamilton 2020).

A Growing Subpopulation

Why?

A Growing Subpopulation

[M]uch of the scholarly research on black immigrants has used the outcomes of this group to elucidate the roles of racism and discrimination vis-à-vis poor cultural practices in patterning the outcomes of black Americans.

(Hamilton 2020, 296, EMPHASIS ADDED)

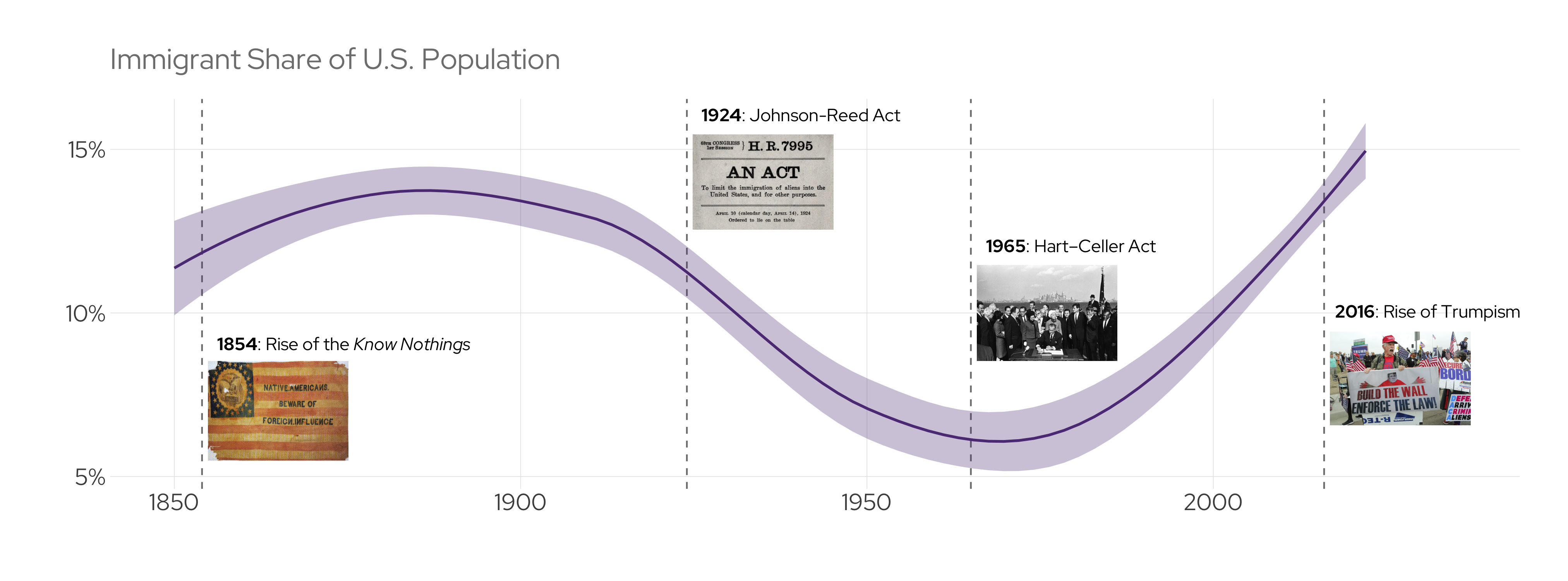

Pre-1965 Black Immigration

Early 20th Century

The flow of black immigrants to the United States—primarily from the Caribbean—began in earnest in the 1910s and 1920s. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, the growth of black immigration to the United States outpaced the growth of white immigration as well as native black population growth (Reid 1939). Moreover, during this period, black immigrants were the largest nonwhite racial/ethnic immigrant group in the United States, outnumbering Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino immigrants (Reid 1939).

(Hamilton 2020, 297, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Early 20th Century

Black immigration to America began to crater around 1924.

Early 20th Century

A Question

What were some of the factors driving the decline?Early 20th Century

Early 20th Century

The decline of Black immigration was, in part, shaped by—

Diffuse anti-immigrant sentiment.

Challenges acquiring visas in the Caribbean and Latin America.

Onset of the Great Depression in America and beyond.

Early 20th Century

In the early 20th century, Black migration from beyond the United States coincided with seismic shifts in the spatial distribution of Black Americans within the country.

The Great Migration

While racism and discrimination were prevalent throughout the country, living conditions were considerably harsher in the South than in the northern states. In the face of these bleak conditions, as well as the draw of industrial jobs in the Northeast, more than 1.6 million black Americans moved from the rural South to industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest between 1916 and 1930, a migration pattern known as the Great Migration.

(Hamilton 2020, 298, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Great Migration

The Great Migration

Amid these transformations, Black internal migrants from the South came into contact with Black international migrants from the Caribbean in places like New York City.

The Great Migration

[D]ata from the complete count files of the US Census show that in 1930 only 27% of blacks living in New York City were born in New York; 61% were born in the United States but outside New York, with most hailing from southern states; and the remaining 12% were foreign born, mainly from the Caribbean.

(Hamilton 2020, 298, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Labour Market Disparities?

In the Early 20th Century

Were there significant advantages for foreign-born vis-à-vis

native-born Black Americans on the labour market?

Labour Market Disparities?

In the Early 20th Century

Hamilton (2019) found no consistent evidence of significant labor market advantages favoring black Caribbean immigrants during this period. The most robust and consistent disparities documented by Hamilton (2019) were those between whites and all groups of blacks, indicating that any unobserved selectivity and/or cultural differences that existed within New York City’s black population in the early 1900s were not pronounced enough to overcome the enormity of racism during the period.

(Hamilton 2020, 298, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion I

The Early Black Immigrant Experience

In groups of 2-3, use assimilation theory to explain the trajectories or lived experiences of early Black immigrants in America.

The Post-Civil Rights Era

Resurgent Black Migration to America

In 1960, approximately 125,000 black immigrants resided in the United States, nearly all of whom had been born in the Caribbean. By 1980, the number of black immigrants had risen to 816,000, a 553% increase in only two decades.

(Hamilton 2020, 300, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Resurgent Black Migration to America

The Black immigrant population grew to more than 1.5 million in the 1980s—due in large part to policy interventions (e.g., Refugee Act of 1980, Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986).

Resurgent Black Migration to America

While much of the growth of the black immigrant population from the 1960s through the 1980s was driven by Caribbean immigration, African immigration became increasingly important beginning in the mid-1990s, with African immigrants accounting for more than half of the flows of black immigrants to the United States during the 2000s.

(Hamilton 2020, 300, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Resurgent Black Migration to America

The shifts in immigration streams that began in the 1990s increased the diversity of the black immigrant population in the United States. Because of the long history of immigration from the Caribbean, since the early 1900s, Jamaica has accounted for the largest flow of black immigrants, followed by Haiti. Indeed, five of the top ten sending countries … of black immigrants are Caribbean countries. The other five are sub-Saharan African countries, highlighting the dramatic growth of the African origin population since 1990.

(Hamilton 2020, 300, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Black Immigrants and Racial Disparities

In the Post-Civil Rights Era

Just as earlier immigration waves stimulated the public and academic debates of the early 1900s, the growth of the black immigrant population in the post-1965 era generated robust debate regarding the root causes of disparities between black and white Americans.

(Hamilton 2020, 300, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Black Immigrants and Racial Disparities

In the Post-Civil Rights Era

Given the persistent disparities between black and white Americans in the post-1965 era and the long-standing view that the accomplishments of black immigrants are evidence that the poor outcomes of black Americans stem from cultural dysfunction rather than racism and discrimination, it is vital to understand the mechanisms that produce disparities between black Americans and immigrants.

(Hamilton 2020, 300, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Three Mechanisms

(1) “Cultural” Differences

Some researchers have argued that distinct historical legacies of slavery in the United States and the Caribbean produced cultural differences that in turn led to social and economic disparities between Caribbean immigrants and native-born blacks.

(Hamilton 2020, 301, EMPHASIS ADDED)

(1) “Cultural” Differences

Scholars have linked these putative “cultural” cleavages to —

Institutional variation in the economic organization of slavery in the American South vis-à-vis the Caribbean.

Compositional differences between the Caribbean—i.e., where slaves constituted a numeric majority—and the American South—where slaves were a numeric minority.

The psychological benefits accrued to Black immigrants socialized in majority-Black contexts.

(2) White Favouritism

Scholars have suggested that labor market disparities between black immigrants and black Americans result from differential patterns of labor market discrimination … Evidence of differential patterns of discrimination comes from black immigrants who report that white employers have a strong preference for black immigrants over black Americans (Foner 1985), black Americans who perceive worse treatment than black immigrants from white employers (Waters 1999), and white managers who state a preference for black immigrants over black Americans.

(Hamilton 2020, 303, EMPHASIS ADDED)

(2) White Favouritism

Researchers have also suggested that white employers favor Caribbean immigrants over native-born blacks as a result of the latter group’s connection to the racialized history of slavery in the United States. As a result of this connection, black Americans occupy the least favorable position in the US discrimination hierarchy.

(Hamilton 2020, 303, EMPHASIS ADDED)

(3) Selectivity

[B]lack immigrants, like all other immigrants, are self-selected and thus differ systematically from other individuals in their native countries. Those who emigrate often have better health and higher education levels than their peers who stay in the home country … [I]n 2014, 63% of black Nigerian immigrants residing in the United States had at least a bachelor’s degree, while only 7% of the Nigerian population had earned a bachelor’s degree. In the same year, among immigrants from Haiti … the mean length of schooling was 12.27 years, while among individuals living in Haiti it was 5.18. To varying degrees, this type of selection exists among black immigrants from all major sending countries.

(Hamilton 2020, 303, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion II

Explanatory Power of Competing Explanations

In new groups, discuss the relative importance of the three candidate mechanisms detailed in our foregoing discussion.

Group Discussion III

Can Assimilation Theory Help?

In those same groups, draw on Hamilton’s (2020) insights to explain how segmented assimilation theory and neo-assimilationism

can be used to understand disparities between

native- and foreign-born Black Americans.

Lecture II: November 11th

Reminders and Updates

Response Memo Deadline

Your eighth response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM on Wednesday …

Unless …

… you attend the first Cummings Lecture this Wednesday.

Reminders and Updates

The Cummings Lecture

Title

Place, Polarization, and the Future of America’s Political Divisions

Abstract

Click to Expand or Close

Note: Scroll to read entire abstract.

How does place shape America’s polarized politics? Decades of political-economic transformations have reshaped both the kinds of people and the kinds of places that give their support to the Democratic and Republican Parties, hardening political boundaries along lines of race, class, religion, and context. Working-class, ex-urban, and industrial communities that were once the bedrock of the Democratic Party are now the sites of greatest contestation every election cycle, while the affluent suburbs that once fomented conservative activism in the 1950s and 60s are the sites of greatest growth for the Democratic Party. In this talk, sociologist Stephanie Ternullo (Harvard University) will consider the historical causes and contemporary consequences of these shifts in political geography, and the challenges they present for political representation in American elections, including the November 5th presidential election.

Date and Time

Location

Reminders and Updates

Dr. Stephanie Ternullo will join SOCI 229 before her talk. Feel free to join us.

Reminders and Updates

Final Paper Proposal

Final Paper Proposal Deadline

Your final paper proposals are due by 8:00 PM on Friday, November 22nd.

Reminders and Updates

Final Paper Proposal

Guidelines for the final paper proposal can be found here.

Reminders and Updates

Final Paper Proposal

To submit your final paper proposal, click here.

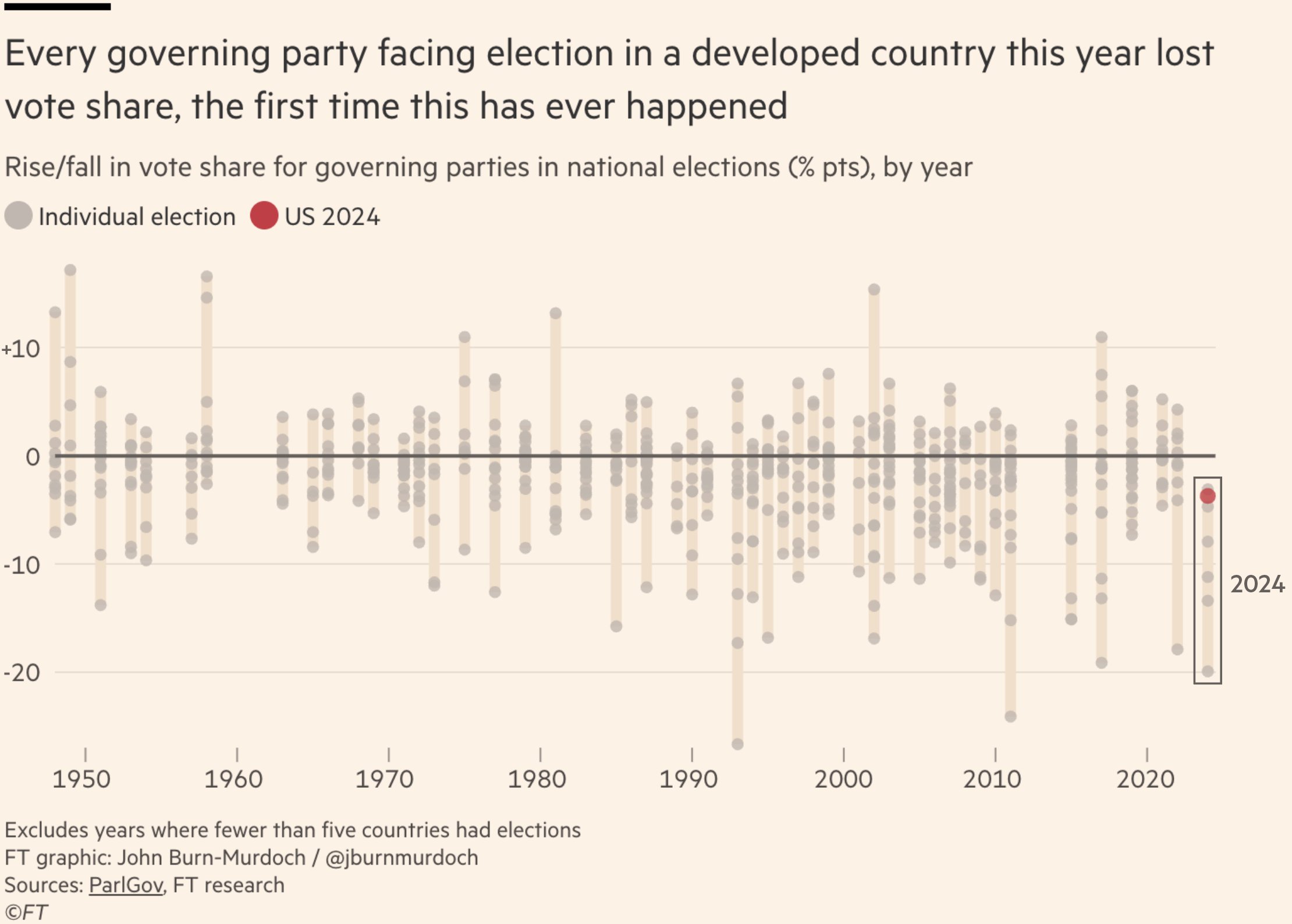

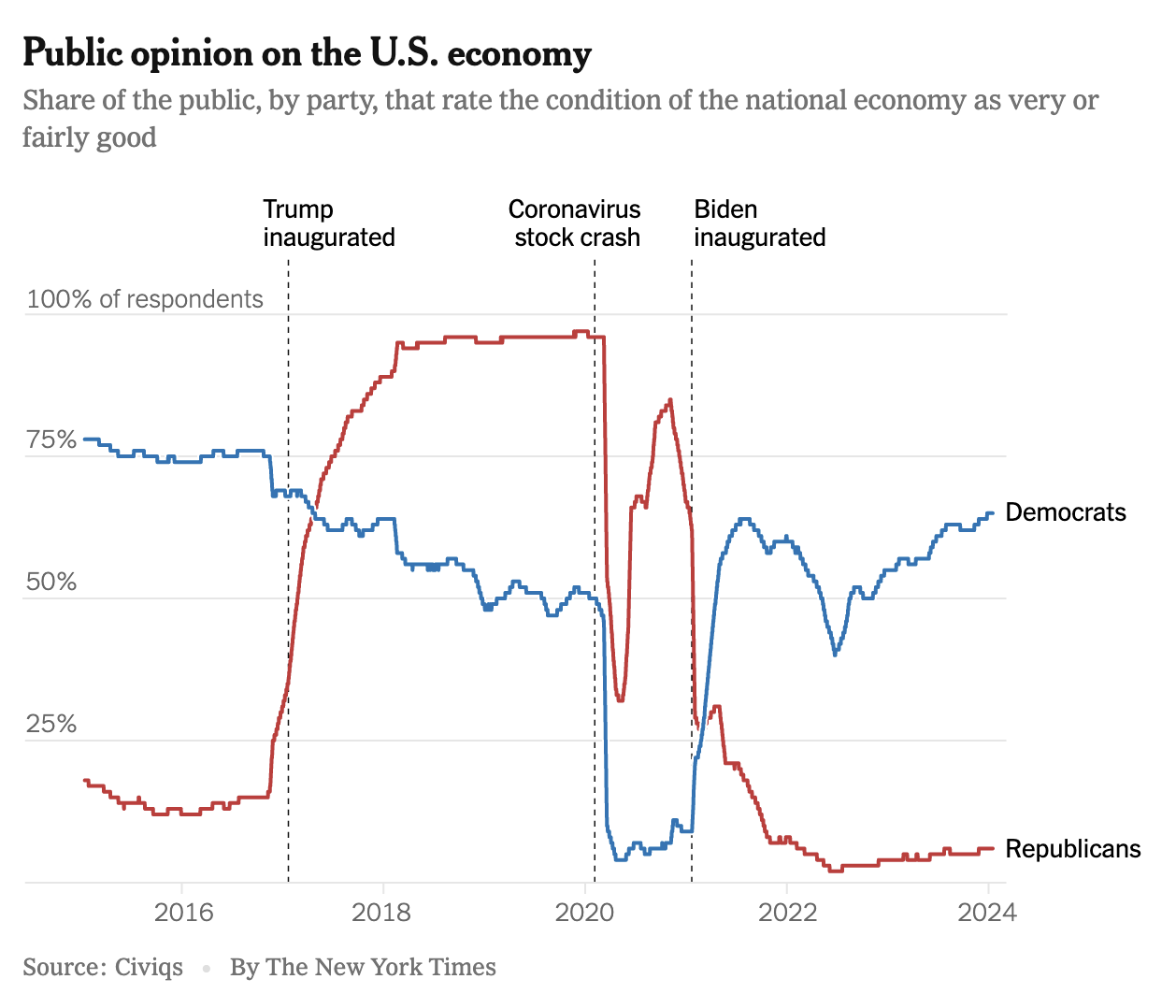

Sidebar—

A Few More Reflections on the 2024 Presidential Election

Once Again—Let the Dust Settle

Once Again—Let the Dust Settle

Working hypotheses are necessary. However, we have to embrace uncertainty and the possibility that our initial hunches are wrong. Falsification is simply not possible in the wake of an election.

Some (Potentially) Useful Charts

Some (Potentially) Useful Charts

Some (Potentially) Useful Charts

A Few Basic Takes

Material economic conditions matter.

A Few Basic Takes

Cultural contestation matters, too.

A Few Basic Takes

A Few Basic Takes

Moreover, exit polls—as noted last week—can be very misleading.

A Few Basic Takes

Worse, they can foment groupism (see Brubaker, Loveman, and Stamatov 2004) and its analytic corollaries: reification, essentialization, homogenization and so on.

A Few Basic Takes

This can lead to faulty inferences and spurious conclusions.

Identities of the Black Second Generation — Mary Waters

Challenging Assumptions

The growth of nonwhite voluntary immigrants to the United States since 1965 challenges the dichotomy which once explained different patterns of American inclusion and assimilation — the ethnic pattern of assimilation of immigrants from Europe and their children and the racial pattern of exclusion of America’s nonwhite peoples. The new wave of immigrants includes people who are still defined “racially” in the United States, but who migrate to the United States voluntarily and often under an immigrant preference system which selects for people with jobs and education that puts them well above their “co-ethnics” in the economy.

(Waters 1994, 795, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Challenging Assumptions

With this in mind, Waters (1994) examines the ethno-racial identities of second-generation Black Americans in New York City (of the early-1990s) with roots in the Caribbean.

Challenging Assumptions

The children of black immigrants in the United States face a choice about whether they will identify as black Americans or whether they will maintain an ethnic identity reflecting their parents’ national origins. First-generation black immigrants to the United States have tended to distance themselves from American blacks, stressing their national origins and ethnic identities as Jamaican or Haitian or Trinidadian, but they also face overwhelming pressures in the United States to identify only as “blacks.”

(Waters 1994, 796, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Invisible Immigrants

Consequently, Black Americans with non-American roots have been described as invisible immigrants.

Invisible Immigrants

[R]ather than being contrasted with other immigrants (for example, contrasting how Jamaicans are doing as compared with Chinese), … (Black immigrants) have been compared to black Americans. The children of black immigrants, because they lack their parents’ distinctive accents, can choose to be even more invisible as ethnics than their parents. Second-generation West Indians in the United States will most often be seen by others as merely “American” — and must actively work to assert their ethnic identities.

(Waters 1994, 796, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Intraracial Divisions

Longstanding tensions between newly arrived West Indians and American blacks have left a legacy of mutual stereotyping (Kasinitz 1992). The immigrants see themselves as hard-working, ambitious, militant about their racial identities but not oversensitive or obsessed with race, and committed to education and family … American blacks describe the immigrants as arrogant, selfish, exploited in the workplace, oblivious to racial tensions and politics in the United States, and unfriendly and unwilling to have relations with black Americans.

(Waters 1994, 797, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Intraracial Divisions

The first generation believes that their status as foreign-born blacks is higher than American blacks, and they tend to accentuate their identities as immigrants. Their accent is usually a clear and unambiguous signal to other Americans that they are foreign born.

(Waters 1994, 797–98, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Intraracial Divisions

The dilemma facing the second generation is that they grow up exposed to the negative opinions voiced by their parents about American blacks and exposed to the belief that whites respond more favorably to foreign-born blacks. But they also realize that because they lack their parents’ accents and other identifying characteristics, other people, including their peers, are likely to identify them as American blacks. How does the second generation handle this dilemma?

(Waters 1994, 798, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Applying Assimilation Theory

Subverting the Straight Line?

(The) “straight line” assimilation model assumes that with each succeeding generation the groups become more similar to mainstream Americans and more economically successful … However, the situation faced by immigrant blacks in the 1990s differs in many of the background assumptions of the straight line model. The immigrants do not enter a society that assumes an undifferentiated monolithic American culture, but rather a consciously pluralistic society in which a variety of subcultures and racial and ethnic identities coexist. In fact, if these immigrants assimilate they assimilate to being not just Americans but black Americans. It is generally believed by the immigrants that it is higher social status to be an immigrant black than to be an American black.

(Waters 1994, 798, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Subverting the Straight Line?

There are, to be sure, other important differences that distinguish the America that inspired straight-line theory from the America that most Black immigrants encountered in the post-1965 era—

Different economic and structural conditions for all workers.

More heterogeneity in the human capital profile(s) of immigrant-origin subpopulations.

More durable and deeply entrenched forms of residential segregation (i.e., along racial lines).

Group Discussion IV

Applying Segmented Assimilation Theory

Identificational Patterns

Three General Types

Waters (1994) identifies three general kinds of identificational profiles that her interviewees acquired—

Black American

Ethnic American (e.g., Jamaican American)

Immigrant (e.g., Haitian)

Three General Types

A Stylized Illustration

Three General Types

In general, the ethnic-identified teens agreed with their parents and reported seeing a strong difference between themselves and black Americans, stressing that being black is not synonymous with being black American. They accept their parents’ and the wider society’s negative portrayals of poor blacks and wanted to avoid any chance that they will be identified with them.

(Waters 1994, 805, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The American-identified second-generation teenagers … follow a path which is more similar to the model posed in the straight line theory. They stress that they are American because they were born here, and they are disdainful of their parents’ lack of understanding of the American social system. Instead of rejecting the black American culture, it becomes their peer culture and they embrace many aspects of it. This brings them in conflict with their parents’ generation, most especially with their parents’ understandings of American blacks. The assimilation to America that they undergo is most definitely to black America; they speak black English with their peers, they listen to rap music, and they accept the peer culture of their black American friends

(Waters 1994, 807, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The more recently arrived young people who are still immigrant-identified differed from both the ethnic and the American-identified youth. They did not feel as much pressure to “choose” between identifying with or distancing from black Americans as did either the American or the ethnic teens. Strong in their identities with their own or their parents’ national origins, they were neutral toward American distinctions between ethnics and black Americans. They tended to stress their nationality or their birthplace as defining their identity.

(Waters 1994, 809–10, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Exercise

A Class Debate

In your assigned groups —

Discuss the first chapter in Orly Clergé’s (2019) The New Noir.

Specifically, discuss how Clergé (2019) uses the concept of diaspora to push back against the assimilation paradigm.

As a group, develop a comprehensive argument in line with your assigned “position” on the persuasiveness of Clergé’s critique of assimilation theory.

After some quick presentations, groups will reconvene to critically

assess the claims put forward by the “competition.”

See You Soon

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography